One hundred years ago this month, a young British Army intelligence officer in Cairo was getting ready for a mission that would change his life.

The war was not going well. On the Western Front the Battle of the Somme had dissolved into a bloody stalemate. In the Middle East things weren't much better. The previous year had seen the failed attack on the Turks at Gallipoli, whilst in April 1916 General Townshend and his army had surrendered at Kut, in modern Iraq. What the nation needed was a hero.

The man who decided he was going to be that hero was T.E. Lawrence. An above averagely talented novelist, he enjoyed an above averagely exciting First World War. Had he kept these talents separate he would now be largely forgotten as both writer and war hero, but by combining them he made himself a legend.

The myth has largely eclipsed the man, but as he mostly invented it himself he can't really complain. So what is the truth?

First,

what didn't he do.

1. Lead the Revolt

|

| Sirs not appearing in this film. |

The Arab Revolt which broke out in June 1916 was nominally led by Ali ibn Hussein, who had been

appointed Emir of Mecca by the Ottomans.

However the actual fighting was done by his sons. Eldest Ali held the southern front around Mecca. Second son Abdullah fought in the east, against both the Ottomans and the rising power of the Saudis. Third son Feisal was in the west. That put him in the better position for getting British help, but his ambitions also made him the more pliable character, and hence the favourite son with His Majesty's government.

A host of British and French officers went to help the Arabs. Colonels Pierce C Joyce and Stewart Francis Newcombe were the vital links during the initial stages of the Revolt, which happened whilst Lawrence was still at his desk in Cairo. When he eventually arrived in Feisel's camp in October 1916 he joined a growing team of European advisers.

Lawrence only become associated with the Revolt in the public eye after the war, when American film maker Lowell Thomas opened his film

With Allenby in Palestine in Covent Garden in 1919. The launch was accompanied by exotic dancing girls and the band of the Welsh Guards, whilst Lawrence posed for publicity shots in Arab costume. The image of the clean-cut hero in the desert created such a contrast to the bloody horrors of the Western Front that it was a huge hit and soon the film was soon being billed as

With Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabia, giving the colonel (as he then was) equal billing with his general.

The Arabs themselves were now only so much colourful scenery. To the public Lawrence now was the Arab Revolt.

2. Pioneer attacks on the railway

|

| Lawrence of Arabia was here |

The tactics Lawrence is most associated with are the daring attacks on the Hejaz Railway. The initial stages of the Revolt involved fairly conventional warfare, but by 1917 the rebels were in a position to attack the Achilles Heal of the Ottoman forces, the slender rail link between Medina and Damascus. Attacking the railway tied up large numbers of Turkish soldiers and prevented the 12,000 troops in Medina from coming to the aid of the rest of the army fighting the decisive battles with Allenby in Palestine.

Initial attacks on the railway line were led by Colonel Newcombe, and then in February 1917 Lieutenant H Garland first blew up a moving train using a mine of his own devising. After that Colonel Joyce was kept busy supplying explosives to attack the line. Lawrence did eventually join in himself, but Newcombe, Garland and Joyce were the pioneers of the tactic. Still, better late than never.

3. Cross Sinai in two days

|

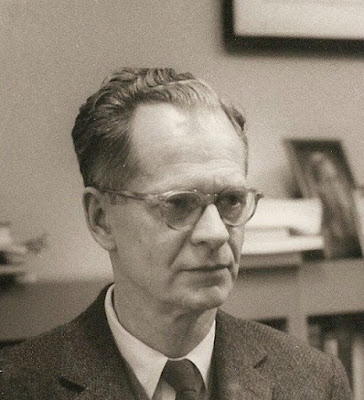

| The real Lawrence |

Amongst the heroics documented by Lawrence in his book

The Seven Pillars of Wisdom is his crossing of the Sinai desert in two days, to bring news of the fall of Aqaba to Allenby's headquarters in Cairo. The adventurer Michael Asher tried and failed to emulate this feat, nearly killing himself and his camels in the process.

Having failed to live up to his hero, Asher took a look closer look at Lawrence's diary. He had scrupulously recorded where he pitched camp every night and this revealed, contrary what Lawrence himself actually wrote, that he crossed the Sinai in a more reasonable, if less remarkable, three days. This is still a pretty impressive adventure, especially in wartime, but it is not superhuman.

4. Lead a picked group of Arabs

|

| Lawrence and his real friends |

The theme of

The Seven Pillars of Wisdom is how Lawrence inspires the Arabs but then in turn is dehumanised by the horrors of war. The trigger for this was apparently when he was captured whilst on a undercover reconnaissance in the town of Deraa. Like most of Lawrence's stories this is highly controversial, although there is no evidence it didn't happen either so we can give him the benefit of the doubt.

The result was a No More Mister Nice Guy approach, and when he next went into battle it was supposedly at the head of a hand picked band of 200 cut-throats

and brigands who had sworn personal loyalty to him, 60 of whom died in his service. The reality, as recorded by those who were there, is rather more ordinary. He had an entourage of about a dozen Arabs who fetched his water, looked after his camels and presumably did his laundry. None were brigands, and none appeared to have actually died in battle.

5. Massacre prisoners

|

| Dramatic license |

The culmination of the new hardcore approach by Lawrence was when he led an attack on a column of retreating Turks in which he ordered that no prisoners were to be taken.

The battle is real enough, and was greatest single success the Arab army had against the Turks, wiping out a column of 1000 men, including Germans and Austrians. Lawrence wasn't the only European present. As well as other British officers there was the Frenchman Capitaine Rosario Pisani, commanding a battery of mountain guns. He'd been on the Aqaba mission too, although without the guns, but someone didn't make it into the film.

What actually happened though is still disputed by historians. What is not in doubt is that the Turks massacred the entire village of Tafas, although whether this happened before or after the battle is disputed. Either way though the Arabs had it in for the Turks. Lawrence later wrote to his brother that he ordered 250 prisoners, including Austrians and Germans, to be machine gunned. Nasty stuff.

However second hand accounts from Arabs officers who were there said Lawrence, and other British officers, tried to stop the killing. Other accounts have Lawrence tell of how he found what he witnessed "sickening". Even his brother didn't believe the claim Lawrence had ordered the prisoners shot, and it doesn't actually appear in Lawrence's own book.

Why Lawrence should portray himself as a war criminal if he wasn't is one of the mysteries of the man. Maybe it was just for dramatic effect or maybe, like many returning soldiers, he really did feel a sense of guilt for his involvement in a war that was nowhere near as clean and honourable as he portrayed it.

So if Lawrence was a minor figure in the Revolt, and a braggart to boot, should we still read his book, or even remember him at all?

Yes, because here are

five things he did do:

1. Understand guerrilla warfare

When British soldiers back in the Middle East in 2001,

The Seven Pillars of Wisdom was being taken down from the bookshelf and dusted off. The reason is that Lawrence, the academic in uniform, understood the nature of the guerrilla war he was engaged in better than the professional soldiers he served alongside.

He wrote of the Arab army being like a 'gas', aiming to avoid pitched battles whilst engaging in hit-and-run tactics that caused maximum disruption with minimum casualties.

'Most wars are wars of contact, both forces striving into touch to avoid tactical surprise. Ours should be a war of detachment. We were to contain the enemy by the silent threat of a vast unknown desert., not disclosing ourselves till we attacked. The attack might be nominal, not directed against him, but against his stuff.; so it would not seek either his strength or his weakness, but his most accessible material.'

The British Army thought it knew how to fight guerrillas, but only Lawrence, the outsider, was able to understand how to be one. Today American Generals read Lawrence so they can understand too.

2. Capture Aqaba

|

| Real photo of the attack on Aqaba |

Not all Lawrence's heroics were made up. His capture of Aqaba was real. The port threatened the flank of the British forces in Palestine and was protected from attack from the landward side by the desert the Arabs called 'al-Houl', meaning 'the terror'. It was defended by three battalions of Turkish infantry.

The film has Lawrence riding off into the desert to persuade Anthony Quinn's Auda to stop taking Turkish money and joint the Revolt. In reality, whilst Auda had accepted Turkish gold in the past, he was very much fighting for Arab independence by this time. Auda was with Lawrence from the beginning of the Aqaba mission and on the way rounded up 6-700 Arabs from his Howeitat tribe for the attack. The operation was at least as much Auda's as Lawrence's.

Director David Lean exaggerates the naval defences of Aqaba, which were minimal, although still enough to keep the Royal Navy away, and misses out the Turkish infantry battalion that was camped round the last well before the port. These were dealt with using classic guerrilla tactics. The Turks were first harassed by snipers until, after a day in the sun being shot at, they were finished off by a charge from Auda. All were either killed or captured. The port then fell with the help of the Royal Navy without a shot being fired.

It was an amazing victory by an irregular force over numbers of superior soldiers, and completely changed the strategic situation. The Arabs were now in a position to threaten the entire length of the Hejaz railway, as well as to move on to Damascus. For this battle alone, Lawrence deserves to be famous.

3. Co-ordinate the Revolt with Allenby

|

| Lawrence and Allenby |

Sir Edmund Allenby arrived in Egypt in June 1917 with a reputation as being General Melchett style bloodthirsty bungler. In the deserts of Palestine though he found he calling, and his imaginative strategy led to him becoming the only genuine hero of the war the British Top Brass produced.

He was a month into the job Lawrence when captured Aquaba. Allenby immediately realised the potential of this act. The idea of coordinating the Arab Revolt with the British advance was Allenby's, not Lawrence's, but it was Lawrence who carried it out.

The Bedouin first of all tied down the Turkish forces, then cut their railway links, and finally covered the right flank of Allenby's army as it advanced on Damascus.

Lawrence's operation were not just with Arab irregulars, and he also led missions that consisted solely of British armoured cars and infantry on camels.

Lawrence was lucky to have such a dynamic general to work with, but he deserves credit both for realising the potential of guerrillas as support for a conventional force, and for actually carrying out Allenby's strategy.

4. Understand the Arabs

Lawrence's problems weren't just military, they were also cultural. He knew the strengths and the

weaknesses of his irregular army. His strategy had to not only take advantage of their mobility, but also cover up their lack of discipline. Lawrence avoided casualties were possible, and kept plans simple.

He also knew what motivated the men to fight. He spoke their language and dressed like them, not just for reasons of vanity, but also because he alone of the British Mission understood their cause and their character.

However Lawrence also knew that he was living a big lie. He told the Bedouin they were fighting for Arab freedom, but he knew that France and Britain were not going to allow this. He negotiated to ensure that the Arab troops led the victorious army into Damascus, but he knew that the locals were going to spot that they hadn't been liberated by his ragged force, but by the heavy artillery of Allenby's men following on behind.

In 1918 European Empires covered almost the entire globe. However Lawrence, at least, realised this might not always be the case.

5. Support Arab independence

|

| Lawrence with Feisel in Paris |

But Arab freedom would not come in Lawrence's lifetime. He knew he had sold the Arabs a lie, but he tried to make amends when the fighting was over.

He accompanied Prince Feisel to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, became an adviser to the Colonial Office and attended the Cairo Conference of 1921. By this time Lawrence was famous, and he tried to use his popularity to help the cause of his Arab friends. At one point he suggested to the French hero General Foch that if he led a French army into Syria, he would lead an Arab one against him.

That didn't happen, and instead the Middle East was carved up to make the failed states whose conflicts make up our nightly news. Peace in Arabia would not be one of Lawrence's legacies.

Instead he left an insightful journal of one of the twentieth century's first successful guerrilla insurgencies, created a new doctrine of desert warfare, that would later be adopted by the Long Range Desert Group and the original SAS in the next world war, and inspired one of the greatest films of all time.

That's quite a life by any standards.

Bibliography

The Seven Pillars of Wisdom by T.E. Lawrence (1922)

Lawrence: The Uncrowned King of Arabia by Michael Asher (1999)

The Arab Revolt 1916-18 by David Murphy (2008)