Land of the Dark Elves

It is twilight, and I am swimming in cool waters. Never mind that an air force of mosquitoes is attacking any exposed flesh, I am in heaven. This is one of the most beautiful places I have ever been. I am in a beautiful lake surrounded by tall pines silhouetted against the evening sky. The trees, the soil, the rolling countryside could be Norfolk, if Norfolk had lakes, and more trees.

But this isn't England. It is Deulowitzer See in Lusatia, a region of Germany near the Polish border; the east of the old East Germany, a place that for the whole of my childhood was invisible behind the Iron Curtain.

I am here with Greenpeace UK, part of an international camp that is hidden under the trees. We are here to help our colleagues in Greenpeace Germany because the lake, the nearby village of Kerkwitz, and the neighbouring villages of Atterwash and Grabko are all under threat from the Swedish energy company Vattenfall.

Heaven or Hell?

There is apparently a local saying "God made Lusatia, but the Devil put coal under the ground". Many environmentalists agree that what lies below the lake is indeed the work of Satan for beneath the water is a seam of lignite, or brown coal, Europe's dirtiest fossil fuel.

During Communism its fumes made the East resemble Mordor. Burnt in power stations and made into ersatz petrol to power Trabants, it polluted the air and water and choked the lungs. Cancer, bronchitis, heart and respiratory conditions were the consequences for the local comrades. Acid rain and greenhouse gases were the consequences for the wider environment.

Marxist/Leninism may have gone, but the lignite remains in use in Germany, as it does in Poland, Bulgaria, Serbia, Kosovo and Greece, a dirty fuel from a different era.

The brown coal is bad

Lusatia and its lakes survived Communism, but they may not survive Capitalism.

|

| Photo: Hanno Bock Wikimedia Commons |

I'd seen what might be in store for the lake earlier in the day. The Jänschwalde mine is an open cast pit the size of a city tended by machines size of skyscrapers. Giant bucket wheel excavators clear away the overburden to reveal the lignite lying a few metres below. 'Overburden' is a mining term. To the rest of us this means topsoil, trees, villages, and lakes.

The scale of Jänschwalde is hard to comprehend. From the coach the mine first appears as a wall of earth covering the entire horizon. Looking into the mine you see nothing of human scale.

To turn Deulowitzer Lake into this seems a crime against both God and Nature.

Decarbonising Europe

.jpg) Ironically the problem has partly come about because of the

success of the German Greens. The country was home to an arsenal

of nuclear weapons during the Cold War and dusted with fallout from

Chernobyl in 1986. Anti-nuclear groups in Germany were popular and well

organised and so when Fukushima went bang the country decided to phase out

its nukes.

Ironically the problem has partly come about because of the

success of the German Greens. The country was home to an arsenal

of nuclear weapons during the Cold War and dusted with fallout from

Chernobyl in 1986. Anti-nuclear groups in Germany were popular and well

organised and so when Fukushima went bang the country decided to phase out

its nukes.Although a world leader in renewable power, the German economy is as power hungry as any in the world and so the politicians looked to lignite to fill the gap. But turning to the brown coal threatens to blow the European Union's targets for tackling Climate Change out of the water. Lignite produces at least twice as much carbon dioxide per unit of electricity as gas, and nearly twenty times as much as wind power. The new mines would lock Germany into lignite use until 2050, meaning we can kiss goodbye to keeping Global Warming to two degrees by 2100.

Despite the support of local politicians, and despite a Greenpeace organised referendum in 2009 in which the population of Brandenburg rejected lignite, in April this year the state government approved the plans to expand Jänschwalde. Meanwhile, just across the river that marks the Polish border state owned energy company PGE also wants to start mining for the brown coal.

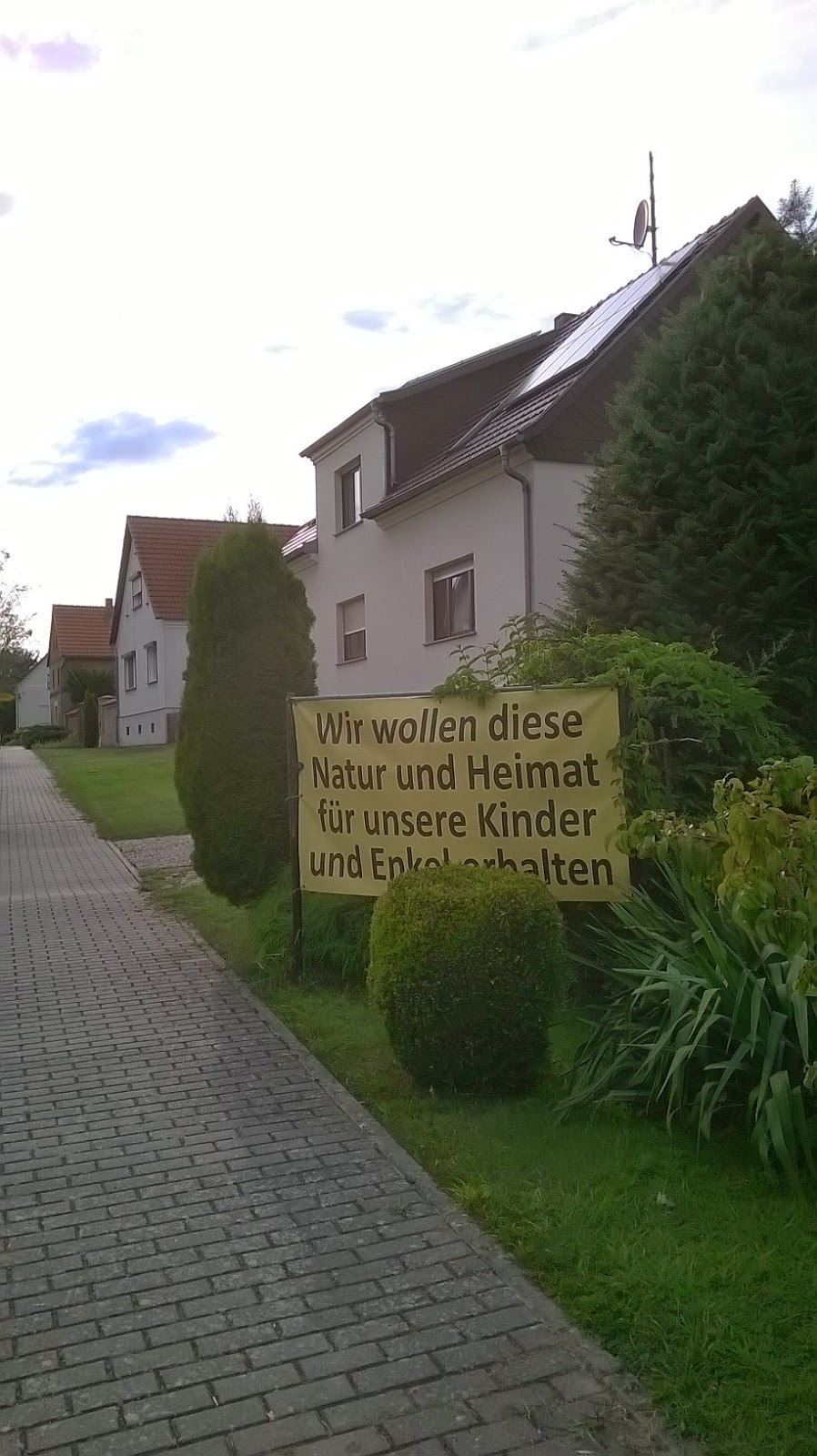

So the battle is on to save both the lakes and the climate. For Pastor Matthias Berndt of Atterwasch this is a spiritual war "We're not just fighting to save our property here in these three villages, we're fighting against the destruction of nature and for the preservation of God's creation."

The Human Chain

.jpg) But the pastor and his flock are not the only people worried about dirty fuels.

But the pastor and his flock are not the only people worried about dirty fuels.Having failed to kill coal with their referendum, Greenpeace Germany organised the Menschenkette, or Human Chain. The plan was to get enough people to come together to make a line 8 kilometres long from Kerkwitz in Germany to Grabice in Poland spanning the width of the proposed mines.

Greenpeace groups from across Northern Europe were taking part, and so on the Thursday before the August Bank Holiday I was with 63 other people from Greenpeace UK on a coach to Kerkwitz.

We travelled through the night along the autobahn passing massive coal fired power stations, but also gigantic wind farms; onshore turbines the size of the largest offshore arrays in the UK.

Last time I passed through this area was more than twenty years ago. Then everyone drove Ladas and Warburgs and there were still Russian soldiers about. Now it is all BMWs and Mercedes and in the high-tech motorway services the toilet seats revolved.

%2Bcropped.jpg) Deposited in the woods by the lake, we pitched our tents next to French, Norwegians, Czechs, Belgians, Dutch and Germans from the west of the country. Our own party, being typically Greenpeace, included at least four other nationalities in addition to British. (Never confuse real Greens with Little Englanders; we are an internationalist bunch.)

Deposited in the woods by the lake, we pitched our tents next to French, Norwegians, Czechs, Belgians, Dutch and Germans from the west of the country. Our own party, being typically Greenpeace, included at least four other nationalities in addition to British. (Never confuse real Greens with Little Englanders; we are an internationalist bunch.)We were knocked out by the beauty of the forest, the quality of the beer and the warmth of the reception. Slightly less so by the lentil soup, admittedly, but you can't knock free food.

Standing in line with seven and a half thousand other people is a bit like being one yeast cell in barrel of beer; you know something great is happening, but it's kind of hard to tell what. This video clip gives some idea of the scale of the protest. I appear at 8 minutes and 42 seconds, which puts me more-or-less in the middle of the chain.

Without a doubt this is the biggest environmental demonstration I've every been on, five or six times bigger than our Manchester fracking rally. It was also one of the friendliest. A couple of die Bullen - as we're apparently supposed to call the police - were seen leaning on their squad cars smoking cigarettes, but basically we didn't need anyone to tell us what to do.

.jpg) Once we were unchained we headed across the border into Poland for a gig headlined by our own Asian Dub Foundation. However we didn't drive for twenty hours from Islington in order a see a band from Hackney, so I don't see the set out and instead head back to Werkwitz.

Once we were unchained we headed across the border into Poland for a gig headlined by our own Asian Dub Foundation. However we didn't drive for twenty hours from Islington in order a see a band from Hackney, so I don't see the set out and instead head back to Werkwitz.Most people are chilling in the Climate Camp and the rest of the UK contingent are drinking the bar dry, but I walked into the village to the meet the locals.

In the Biergarten of the local pub I meet a man who speaks fluent drunk, the parents of the German member of our party and a folk singer who seems to want to sing a duet with me. The live musician struggles to play some English songs on his synthesiser and everyone is pleased to see us. Having spent most of the last decade wondering if their homes are going to disappear into a giant hole it's not surprising.

Tonight, at least, they seem hopeful for the future.

Politician’s Promises

.jpg) Across the border in

Poland Zbigniew Barski, the mayor of

Gubin, was equally happy. “Never has our

problem been so widely reported,” he said. However as we headed back home –

having my passport checked for the only time on the entire journey when

boarding the ferry to England –both the Polish government and the Brandenburg

region seemed unmoved by our protest.

Across the border in

Poland Zbigniew Barski, the mayor of

Gubin, was equally happy. “Never has our

problem been so widely reported,” he said. However as we headed back home –

having my passport checked for the only time on the entire journey when

boarding the ferry to England –both the Polish government and the Brandenburg

region seemed unmoved by our protest.

However, across the Baltic in

Sweden they were having a General Election. Vattenfall wasn’t just a Swedish

company, it is wholly owned by the Swedish government. The Human Chain had the

Swedes talking about brown coal for the first time and opinion polls showed

three quarters opposed the new mines. As these were effectively Vattenfall’s

shareholders, this mattered.

On a TV debate the

leaders of the eight largest parties all indicated they would stop Vattenfall

if elected. But would they keep their promise when in power or wriggle out of

them, possibly by part privatising the company?

When the votes were counted the

centre-left Social Democrats were the largest party, but to form a government

they needed a coalition partner.

They chose the Green Party who had two

demands for them. The second was an end to nuclear power, but the first was

stopping Vattenfall.

Old problems

It's been said before that environmentalist have been fairly successful in tackling the bad new things of the late twentieth century such as nuclear power, DDT, GM food and - in Germany at least - fracking. However we've been completely useless at stopping the bad old things of the early twentieth century such as cars, chemicals and most of all coal.

Hopefully The Human Chain has done something to redress the balance. Brown coal is bad no matter which way you look at it.

|

| Photo: Gordon Welters/Greenpeace |

I've camped in some beautiful places in my life only to see them destroyed - the woods near Newbury and the Bollin Valley near Manchester Airport come to mind. This must not happen here.

For the sake of the climate, of the health of the people of Lausitz, but most of all for beauty's sake, let's unite against coal, the future is renewables.

+(198).JPG)

+(199).JPG)

+(218).JPG)

+(215).JPG)

+(205).JPG)

+(190).JPG)